Soapbox: Putting pressure on the supply chain for a sustainable future

Canned Wine Group chief commercial officer Ben Franks says the trade should be leveraging its buying power to bring about a sustainable future

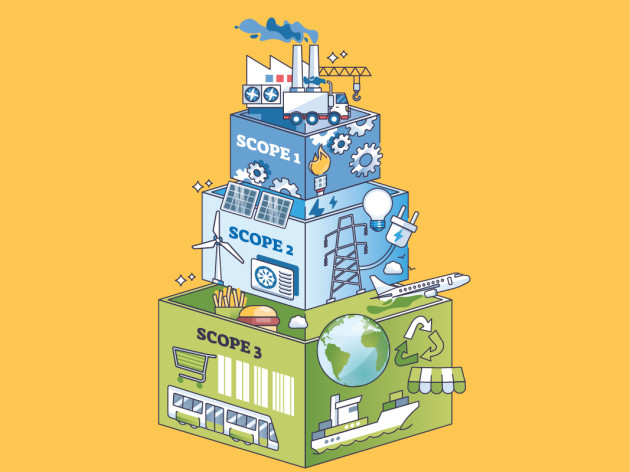

Scope 3 emissions is the category used to account for greenhouse emissions that are outside of a company’s direct control, accounting for both upstream and downstream emissions, which is why they’re also known as ‘value chain emissions’. Because they’re not directly controlled by the business, it often means they can drop in priority for a business’ sustainability strategy. Scope 1 (a company van’s fuel or office waste) and 2 (energy use, for example) can be an easier place to start.

But one of the significant categories defined by the UN’s Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol on Scope 3 is a business’ purchased goods and services, and research from the US-based Environmental Protection Agency says these can often represent most of a company’s total greenhouse gas emissions. At the Eco Drinks conference in January, the figure for agriculture was as much as 90% of a drinks business’ emissions.

Net zero requires a mass, collective reduction in our carbon emissions. If we want to exact genuine change, ignoring 90% or more of your business’ impact is fruitless. Most wine businesses in the UK are importers, so this high Scope 3 figure is going to be common. But when those emissions are outside your control, what are you supposed to do about it?

Buying power. The adage of ‘voting with your wallet’ is born from truth. Impact, in a capitalist global economy, is driven by financial and growth incentives. It’s why expanding on ESG+ goals is easier for profitable, financially stable businesses. It’s also how bigger business can make a true impact. Traditionally, this buying power is focused downstream on the retailer or venue, who might today use their buying power to demand CO2 emissions savings. This is a start, but the efficacy of the trickle back upstream is too slow. We forget the buying power wielded by the agencies, importers and traders in the middle. Large importers could influence their supply chain in favour of suppliers actioning real change in their viticulture.

For many, a byword for sustainability might be ‘organic’. But in reality, organic rarely makes sense for everyone. Your use of land to output is larger, and you will find yourself spraying more copper in marginal climates like northern Europe because disease pressure is too high.

It was interesting listening to a talk by fertiliser manufacturer OCI Global at Eco Drinks, which saves on CO2 emissions for one of conventional farming’s most used products – ammonia-based synthetic fertilisers. The company is also investing in blue and green ammonia as a cleaner way to impact use of synthetic fertilisers in the future. This would allow growers to meet their yields and demands, while cutting emissions.

This approach to cleaner energy is also reflected in the way many wineries are pushing for greener power, investing in solar panels or wind. But all this costs money. Whether innovation in the land, from cover-cropping and agroforestry to drip irrigation, or the winery, investing in regenerative energy or efficiency with the likes of heat pumps all have a substantial capital expenditure. That is why it’s so important for bigger wineries to lead, and why those larger businesses importing their wines must pick and choose those that deliver on change as well as their pricing. It is the importers that can give those wineries the financial sustainability they need to lead.

Europe, often described as a ‘wine lake’ because of years of over production to meet growing demand that’s now falling, is a buyer’s market. The ability to incentivise those competing to deliver value is there for the taking. Importers will talk about price and quality, but let’s add sustainable innovation and make it a must, not a nice to have.

While consumer demand for sustainability is growing, it hasn’t quite gone mainstream – research from Kantar for Diageo suggested only 12% of consumers would pay more for sustainability perks and only 24% were actively making buying decisions on sustainability. Yet Global Data suggests sustainability is important in a brand for 44% of consumers.

This should reflect the conversations buyers are having while looking to leverage change. It’s not about cutting brands and rehashing your book, it’s about having a genuine, holistic conversation with suppliers and encouraging them to implement a plan for change. It might take time. The important part is committing to do it and being prepared to go elsewhere if they don’t change. By starting now, we bring forward the timeline for real impact.