Plotting the indigenous jewels on Hungary’s wine map

Hungary has come a long way since the heyday of Bull’s Blood in the 1970s. Now it’s rich tapestry of indigenous styles are finding their feet

Hungary is place where you will find plenty of words like the ‘biggest’ and the ‘most’.

The Danube, Europe’s second longest river, splits the country in in two – its northerly banks not so far from Lake Balaton – Europe’s biggest lake.

It can also lay claim to one of the oldest winemaking cultures in Europe.

The Hungarian word for wine, ‘bor’, which shares not a scrap of rootstock with the Latin word ‘vinum’, has led historians to conclude that Hungarian wine predates that of Roman interference.

Once home to a rip-roaring wine trade, political upheaval and the sweep of Phylloxera in the late 19th century dampened much of Hungary’s production, although it managed to keep more of a connection to its historic grape varieties than some of its neighbours.

In 2018, this Old World gem of country is therefore ripe with varietal wines and blends from grapes like Furmint, Jufark, Cardarca, Kefrankos (aka Blaufränkisch), which blend traditional and modern sensibilities to provide point of difference wines of quality, with a fair amount of value for money in there too.

For Eastern European wine specialist Caroline Gilby MW, much of Hungary’s outward momentum at present is about establishing the country’s “quality credibility”.

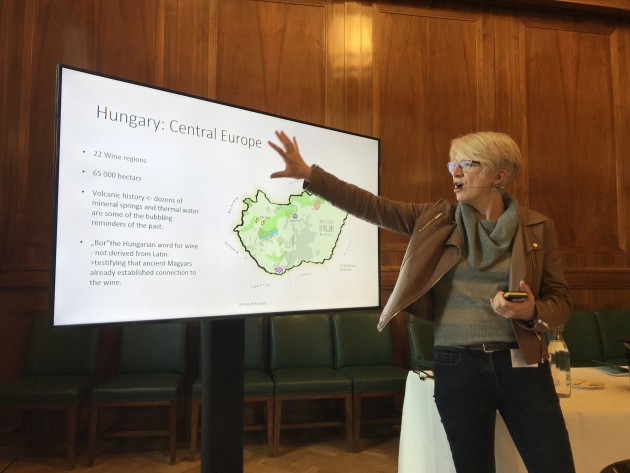

Gilby, who gave a talk on Hungary’s little known grape varieties at Harpers’ SITT event last week, took participants on a whistle-stop of the most UK consumer friendly styles from Hungary’s eye-watering number of varietals, of which 93 white grapes and 50 red can be grown for commercial production - many of them specific to Hungary.

“This is a country that has a long and authentic history going back to when it was founded in 896. Its vineyards are based on volcanic sub-rocks that are divided into 22 distinct regions, each with their own distinctive terroir," she says.

It is this darkly bubbling countryside, rippling with natural spa springs and extinct volcanoes (there are believed to be 5,000 in Tokaj alone) that gave birth to Bull’s Blood, an intense red wine blend with main variety Kékfrankos (Lemberger), replacing Cadarca in recent years.

The wine, which can be made in either Eger or Szekszárd and will be most familiar to consumers as Egri Bikavér (literally ‘Bull’s Blood of Eger’) on labels, has been revived by the likes of Lidl in recent years, with a fair amount of nostalgia stirred into the mix.

Gilby however, points to a more earnest revival.

“By the end of 1980s, Bull’s Blood was made of blends of odds and ends not good enough to make into varietal wines,” she said.

“Winemakers realised that blends were the best way to express a sense of place and there has been quite a lot of effort being put into reviving Bikavér as PDO in Eger as Szekszárd which are the only places where you can make this style of wine.”

St. Andrea is an example of a producer which is driving the idea of blends with his Aldas Egri Bikavér, currently available at the Wine Society for £11.50 and wholesale through Mathew Clark at £9.50.

For Ostorosbor, the biggest winery in Eger, Bikavér remains its flagship and best selling wine.

However, it is also putting as much backing into its Egri Csillag (‘Star of Eger’) – a white and much younger style of wine which was created in 2010 to create an equivalent white cuvee to Bikavér.

Ostorosbor’s Egri Csillag presented at the tasting, a blend of Királyleányka, Leányka, Olaszrizling and Chardonnay grapes to name a few, was noted by Gilby for its fragrant and spicy aromatics, helped by the inclusion of Cserszegi fűszeres, which literally means “spicy”.

White accounts for 60% of total production in Hungary.

And although the country’s sweet Tokaji wines are the only whites to have really branched out beyond its borders, Hungary is the place to look to for whites rising stars says Gilby: “Bianca has come from nowhere recently to top charts. It’s a very forgiving grape, and can survive on harsh plains.”

But when it comes to the “next big thing” dry Furmint, which is a fairly recent development following experimentation with the grape in the 1990s, is Hungary’s star player: “Furmint is incredibly versatile, from sparkling to complex dry wines in the Chablis style or more oaked."

Jufark meanwhile, is notable for being anchored in the tiny southern wine region of Somló, where producer Kolonics makes a single varietal wine from equally tiny plots on the slopes of an extinct volcano.

Kolonics Juhfark 2013 was singled out for its mineral rich and savoury profile and its food matching capabilities.

Which brings us once again back to reds.

Once the anchor of traditional Bikavér blends, Cadarca has fallen out of fashion in recent years to be replaced largely by Kekfrankos and Portugieser.

Kekfrankos, notably, has seen its origins confused with the shifting geography of the region, although it’s believed to have originated in a part of Slovenia which would have once been part of Old Hungary – and according to Gilby, has been underused ever since.

“Hungary has missed a trick with Kekfrankos. It’s the same grape as Blaufränkisch which is big business in Austria, but Hungary has more than anywhere – twice as much as Austria.”

Growing to prominence during Hungary’s forty years as a communist state, it has benefitted in more recent times from a move to keep yields low.

The result says Gilby, is “something completely different. Kekfrankos makes great quality wines, but you have to treat it like Pinot Noir rather than Cabernet and don’t over-extract.”

When it comes to awareness and receptiveness in the UK, consumers will likely be more familiar with Hungary via the likes of the popular I Heart range from Copestick Murray – although via Pinot Grigio, not a food-matching friendly Juhfark or dry Furmint.

But with the endorsement of the likes of Copestick Murray and buyers increasingly looking to Eastern Europe for alternatives to well-known grapes, Hungary’s varietal mix offers a wealth of options waiting to be mined.