Coronavirus: Cash crisis relief too slow

A delay in (and confusion around) relief payments is putting significant pressure on sector notoriously dependent on cash flow. Jo Gilbert reports

When wage subsidies will be paid, whether SMEs will be green-lit for the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS) and if statutory demands will still apply under the rent forfeiture moratorium – these are just some of the issues businesses are grappling with as they face the new world put into motion by the coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak has become the unlikely hero of this crisis, rising from relative obscurity to put in place a widely praised wage safety net for both PAYE businesses and the self-employed via the Job Retention Scheme (JRS).

However, several major question marks still hover over the relief packages that have been put into place by government, with calls for these measures to become more swift and accessible, or face widespread collapse. Faced with income falling to zero overnight, restaurants and bars in particular now find themselves uniquely vulnerable to the current situation, which has left them with no choice but to cease trading.

So far, there has been some assistance offered by the pause of VAT. From 20 March to 30 June 2020, businesses won’t have to pay VAT (deferred until end of tax year 2021), which will help to boost cash flow. There is also the 12-month business rates holiday for all businesses, regardless of rateable value, removing the previous £51,000 cap.

But even with these measures in place, businesses will still have to foot the wage bill for furloughed employees until they are reimbursed by the JRS (to be backdated to 1 March, with first payments going out, at the earliest, at the beginning of May).

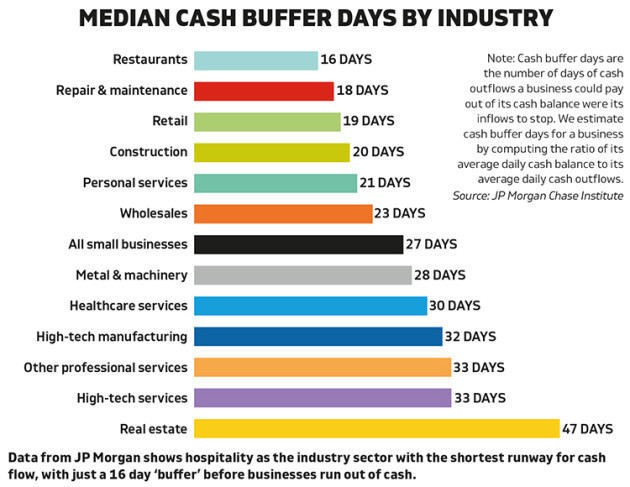

And with suppliers and landlords to pay too and an average of only 16 days cash flow per business (see infographic), restaurants and bars in particular now find themselves especially exposed.

The results may be too much for many, says Vagabond MD Stephen Finch: “The government made a big fuss about imploring businesses to not lay people off and it’d do whatever it takes. It is to be commended for its efforts, but the timing must be better.

“Otherwise businesses that tried to hold on to furloughed staff will have no choice but to lay people off, and of course, it takes cash to lay people off. Make no mistake, very few businesses will have loads of cash lying around.”

With income being “completely paralysed” for some businesses by the current situation, many are now having to make difficult decisions around what to prioritise.

According to property lawyer Paul Jagger, many are being forced to reassess the traditional “30, 30, 30” rule. For the 30% of turnover that is usually spent on goods, payments are being “mainly worked out with suppliers”, while 30% for wages is being ring-fenced. This leaves 30% for fixed costs and rent to deal with – the latter of which is increasingly becoming the major sticking point for businesses.

“The rent forfeiture moratorium is providing breathing space for companies by allowing them to not pay rent for three months without risk of eviction,” says Jagger, partner at hospitality specialists Glover Solicitors.

“However, landlords can still utilise Commercial Rent Arrears Recovery (CRAR), and issue statutory demands, which is a precursor for a winding up petition to force a company into insolvency.”

↓

Law changes

Since the coronavirus outbreak, the government has announced that it intends to make changes to insolvency laws.

Jagger says it is also unlikely in the current climate that a landlord would choose to seize goods via CRAR unless they are specifically trying to remove troublesome or inconvenient tenants.

“Some landlords are being reasonable and cancelling rent payments for the quarter,” he adds.

However, more protection is now being called for within the trade to protect commercial tenants, particularly as a growing number of hospitality names are facing legal action, including Caffe Concerto, which operates 37 sites and is facing a petition over a £100,000 rent bill.

“The rent forfeiture moratorium is deeply flawed,” says Finch. “The government passed the rent forfeiture moratorium to encourage landlords and tenants to negotiate a settlement. Because other coercive options like CRAR exist,objective is ephemeral at best.”

What’s clear is that, when it comes to debt, we’re in uncharted territory.

As businesses close through no fault of their own (“If you’re cut off, what do you continue to owe in a world where you get no money?” asks Jagger) the knock-on effect for suppliers is palpable.

“When the government shut down the on-trade, almost all of our customers stopped paying immediately,” Troy Christensen, CEO of major on-trade supplier Enotria & Coe, told Harpers.

“In some instances we received polite notes informing us that they’d get back to us after 60 days when they expected to reopen. The day after the announcement, 95% of our shipments to customers of their orders were rejected.”

Christensen and Finch were among several people spoken to for this article to take aim at government programmes paying lips service to cash flow problems.

This includes the “ballyhoo’d £300bn” made available through the CBILS, which is unlikely “to find its way to deserving SMEs, particularly not in the time they need it”, says Finch.

“The fundamental flaw is trying to route the funds via the banks. It really needs to be direct from the Bank of England.”

Then there are the cash grants, which are only available for properties with a rateable value of £51,000 or less, which will exclude most London businesses.

There’s no doubt that the current situation is a major headache for the trade, and one that may, in the end, only be relevant for a few months before falling by the wayside.

What’s clear is that many will be keen to keep relationships intact in the hope that they will able to pick up where they left off once lockdown is in the rearview mirror. There’s a hell of a lot of good will out there. In the end, that’s what will see many businesses through these trying times.